EU-Atlas: Dementia & Migration

| Largest group | 2. largest group | 3. largest group | 4. largest group | 5. largest group | |

| Absolute numbers | |||||

| PwMD per 100,000 inhabitants 65+ |

| Absolute numbers | PwMD per 100,000 inhabitants 65+ | |

| Largest group | ||

| 2. largest group | ||

| 3. largest group | ||

| 4. largest group | ||

| 5. largest group |

| Prevalence per 100,000 inhabitants 65+*, calculated by country of residence | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| high > PwMD |

minor > - PwMD |

||

| increased > - PwMD |

low ≤ PwMD | ||

| medium > - PwMD |

|||

| PwMD = People with a Migration background with Dementia *Bulgarien, Litauen, Malta, Polen in der Bevölkerung 60+ |

|||

| Absolute number of PwMD 65+ | |

| PwMD per 100,000 inhabitants 65+ |

Austria

Austria has a long history of migration, characterized by phases of emigration of smaller population groups, but mainly by immigration and transit migration1 due armed conflicts, bilateral labor recruitment agreements, and the EU accession1,2,3. Immigration to Austria reached its peak during the wave of large-scale migration of refugees in 20153. The migrant population (born abroad, 793,200 to 1.8 million) and its proportion in the total population (10.3 to 19.9%) roughly doubled between 1990 and 20194.

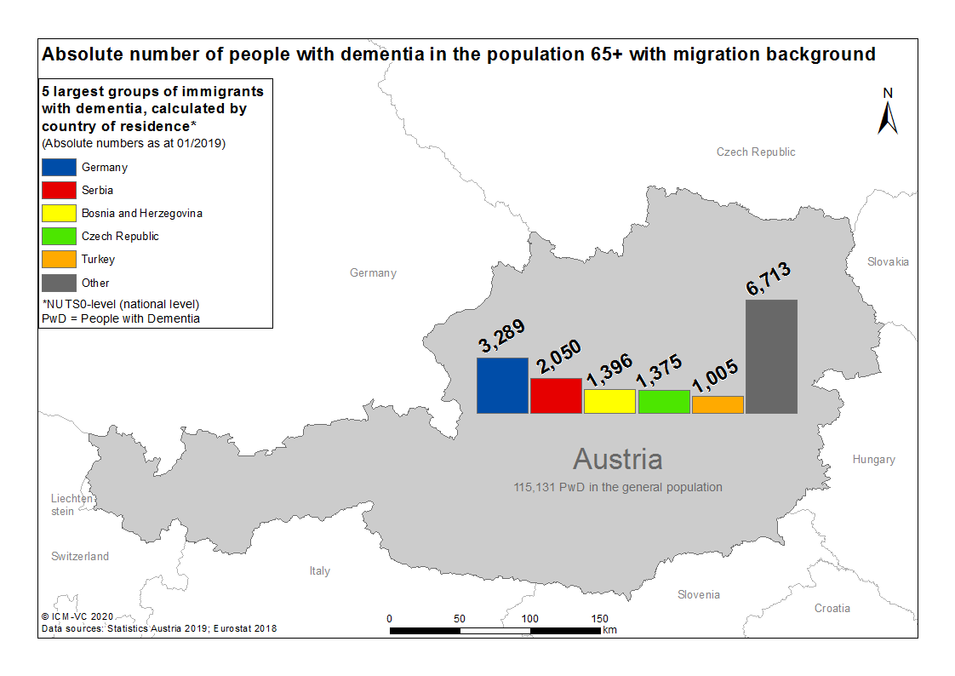

There are 229,400 people with a migration background aged 65 or older. Of those, approx. 15,800 are estimated to exhibit some form of dementia. Calculations show the most affected migrant groups presumably originate from Germany (approx. 3,300), Serbia (approx. 2,000), Bosnia and Herzegovina (approx. 1,400), the Czech Republic (approx. 1,400), and Turkey (approx. 1,000)5.

The ‘Austrian Dementia Report 2014’ from 2015, has a separate chapter on ‘migrants with dementia’. It comprises four pages and points to the problems of a later diagnosis and the lower utilization of care services6. The ‘Dementia Strategy - Living Well with Dementia’, by the Bundesministerium für Arbeit Soziales Gesundheit und Konsumentenschutz, from 2015 contains seven impact goals and 21 recommendations for action. However, none of those goals and recommendations directly relate to migration. In only two passages, access to support services is demanded and multilingual information events are recommended7. The ‘Medical guideline for the integrated care of dementia patients’ from 2011 briefly touches migration in two sentences in one chapter without explicitly addressing it. It is pointed out that neuropsychological tests must consider the socio-cultural background and language skills of a person8. The report ‘Non-drug prevention and therapy for mild and moderate Alzheimer's dementia and mixed dementia’ was published in 2015, but it does not refer to migration on 241 pages9.

Sufficient multilingual information material on dementia is available and there are institutions, which provide multilingual counseling, support, and mediation services for migrants. Nevertheless there are only a few specialised services for migrants with dementia. Currently, there are no nationwide interpreting services in Austria. However, there are nationwide standards for inpatient care regarding the consideration of religion-based food needs, culture-specific needs during family visits, and language needs.

Specific courses on culturally sensitive care and professional training and further education opportunities in intercultural care for doctors and nursing staff exist but these are only optional courses. The proportion of migrants (in inpatient and outpatient care) among caregivers is at least 14 to 15%. Overall, the need for culturally sensitive care is not met by sufficiently qualified professionals.

Family caregivers of migrants with dementia receive the same specific information material (in the respective mother tongue) as non-migrant family caregivers. There is also no significant difference in the provision of other support services. Still, the need for specialized services and information for this population is very high and very diverse.

References

- Jandl M, Kraler A: Austria: A Country of Immigration? [https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/austria-country-immigration]. (2003). Accessed 21 May 2019.

- Bauer WT: Zuwanderung nach Österreich. In. Edited by Österreichische Gesellschaft für Politikberatung und Politikentwicklung. Wien; 2008.

- Bischof G, Rupnow D: Migration in Austria vol. 26. Innsbruck: innsbruck university press; 2017.

- International Organization for Migration: International migrant stock as a percentage of the total population at mid-year 2019: Netherlands; 2019.

- Statistics Austria: Statistik des Bevölkerungsstandes. In. Vienna: Statistics Austria 2019.

- Höfler S, Bengough T, Winkler P, Griebler R: Österreichischer Demenzbericht 2014. In. Wien: Bundesministerium für Gesundheit und Sozialministerium; 2015.

- Arbeitsgruppen 1-6: Demenzstrategie - Gut leben mit Demenz In. Edited by Bundesministerium für Arbeit Soziales Gesundheit und Konsumentenschutz. Wien: Gesundheit Österreich GmbH; 2015.

- Dorner T, Rieder A, Stein K: Besser Leben mit Demenz: Medizinische Leitlinie für die integrierte Versorgung Demenzerkrankter. Wien: Competence Center intregrierte Versorgung; 2011.

- Fröschl B, Antony K, Pertl D, Schneider P: Nicht-medikamentöse Prävention und Therapie bei leichter und mittelschwerer Alzheimer-Demenz und gemischter Demenz. In. Edited by Gesundheit Österreich GmbH. Wien; 2015.

![[Translate to Englisch:] Logo RBS [Translate to Englisch:] Logo RBS](/fileadmin/_processed_/9/7/csm_RBS_Logo_RGB_0e245a98a4.jpeg)