EU-Atlas: Dementia & Migration

| Largest group | 2. largest group | 3. largest group | 4. largest group | 5. largest group | |

| Absolute numbers | |||||

| PwMD per 100,000 inhabitants 65+ |

| Absolute numbers | PwMD per 100,000 inhabitants 65+ | |

| Largest group | ||

| 2. largest group | ||

| 3. largest group | ||

| 4. largest group | ||

| 5. largest group |

| Prevalence per 100,000 inhabitants 65+*, calculated by country of residence | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| high > PwMD |

minor > - PwMD |

||

| increased > - PwMD |

low ≤ PwMD | ||

| medium > - PwMD |

|||

| PwMD = People with a Migration background with Dementia *Bulgarien, Litauen, Malta, Polen in der Bevölkerung 60+ |

|||

| Absolute number of PwMD 65+ | |

| PwMD per 100,000 inhabitants 65+ |

Finland

Finland does not have a long tradition of international migration. Before the 1990s, the history of migration was mainly characterised by economically motivated emigration. From 1990 onwards Finland developed into an immigration country with migrants from the Russian Federation, Estonia, Somalia, Syria, Afghanistan, and Iraq1. In 2017, people from the former Soviet Union (56,696) represented the largest migrant group, followed by Estonia (46,022), Sweden (32,424), and Iraq (16,254)2. Between 1990 and 2019 the migrant population (people born abroad) has grown many times over (from 63,300 to 383,100)3.

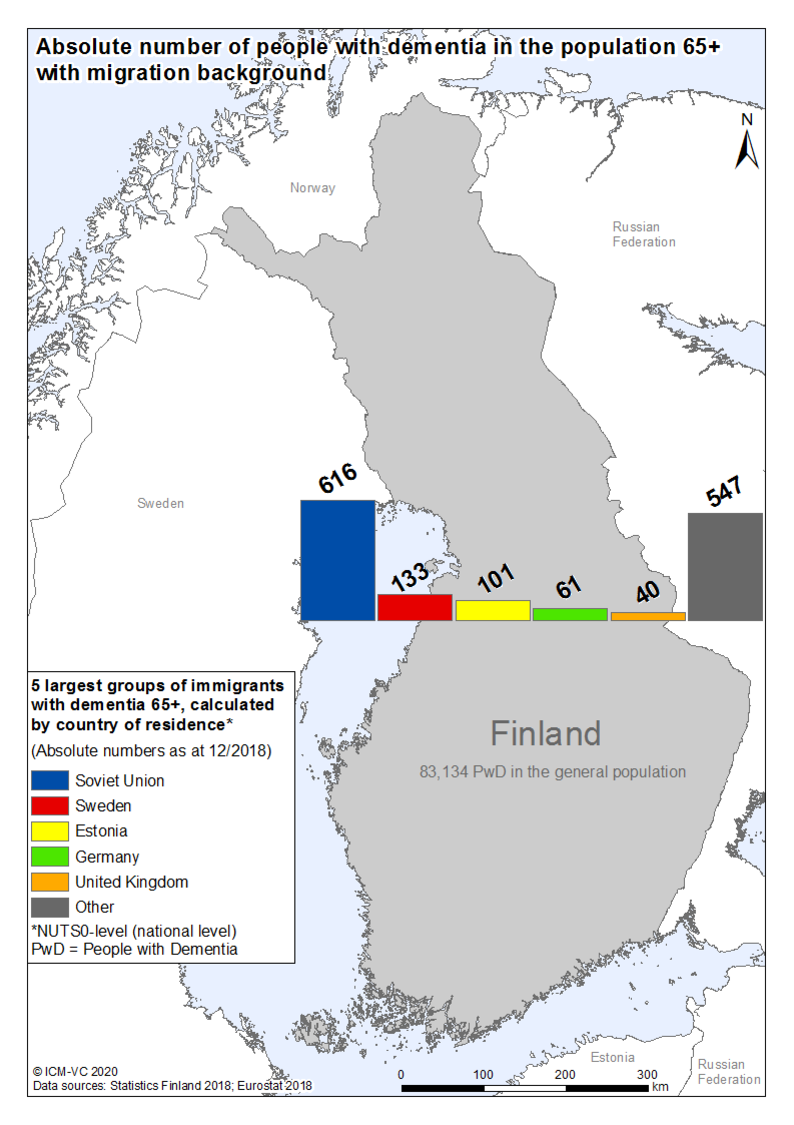

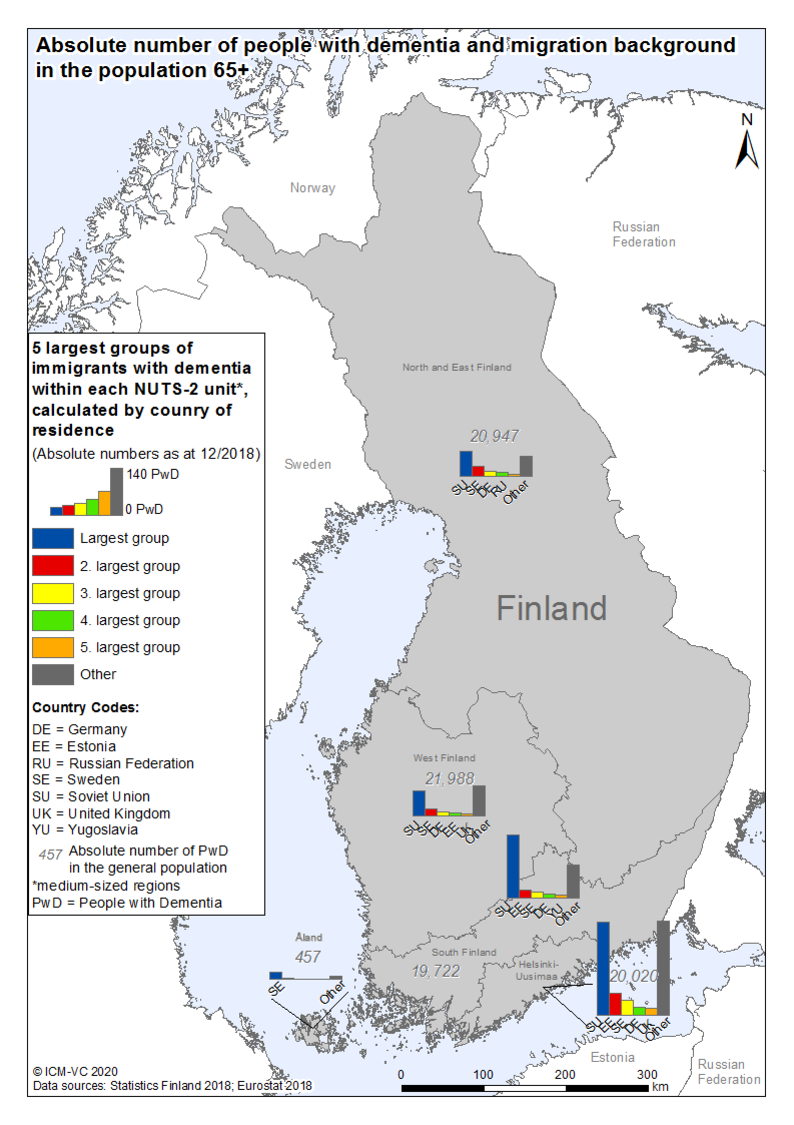

There are 21,700 people with a migration background aged 65 or older. Of those, approx. 1,500 are estimated to exhibit dementia. Calculations show the most affected migrant groups presumably originate from the Soviet Union (approx. 600), Sweden (approx. 100), Estonia (approx. 100), Germany (approx. 60), and Great Britain (approx. 40)4.

The Finish Ministry of Social Affairs and Health has published the ‘National Memory Programme 2012 – 2020: Creating a Memory-friendly Finland’ in 2013 which includes four chapters:

- ‘Brain Health Is a Lifelong Concern’.

- ‘Memory Disorders Affect Us All - Time for an Attitude Check’.

- ‘Proper Treatment and Care Are Worthwhile Investment’.

- ‘More Research and Education Is Still Needed’5.

Furthermore, Finland has publicly accessible treatment guidelines for ‘memory disorders’. This document covers different topics pertaining to memory disorders such as symptoms, incidence, risk factors, opportunities for prevention, diagnosis and evaluation of symptoms, medication, and treatment of behavioural symptoms6. In both documents, the topic of migration was absent.

According to an expert interviewed, dementia and migration is still a fairly new topic in Finland so there is currently a lack of culturally sensitivity in care services and no specialised healthcare services for people with a migration background with dementia are available. Besides, the expert opined that existing mainstream services for dementia are only suitable for non-migrants.

According to the expert, the ability to provide culturally sensitive care is given limited importance in the professional qualification of healthcare workers in Finland. Training for intercultural care is available nationwide but not mandatory anywhere.

According to the expert, the extended family, migrant organisations, religious communities, and service providers play a significant role in supporting family caregivers. Furthermore, there is a high need for specialised services providing support and information to family caregivers of people with a migration background with dementia in Finland.

References

- OECD: Finding the Way: a Discussion of the Finnish Migrant Integration System; 2017.

- Ministry of the Interior Finland: International Migration 2017–2018: Report for Finland. In., vol. 25. Helsinki; 2018.

- International Organisation for Migration: International migrant stock as a percentage of the total population at mid-year 2019; 2019.

- Statistics Finland: Population Structure. In. Helsinki Statistics Finland 2018.

- Ministry of Social Affairs and Health: National Memory Programme 2012-2020: creating a "memoryfriendly" Finland In. Helsinki; 2013.

- Duodecim Käypä Hoito: Muistisairaudet; 2017.

![[Translate to Englisch:] Logo RBS [Translate to Englisch:] Logo RBS](/fileadmin/_processed_/9/7/csm_RBS_Logo_RGB_0e245a98a4.jpeg)