EU-Atlas: Dementia & Migration

| Largest group | 2. largest group | 3. largest group | 4. largest group | 5. largest group | |

| Absolute numbers | |||||

| PwMD per 100,000 inhabitants 65+ |

| Absolute numbers | PwMD per 100,000 inhabitants 65+ | |

| Largest group | ||

| 2. largest group | ||

| 3. largest group | ||

| 4. largest group | ||

| 5. largest group |

| Prevalence per 100,000 inhabitants 65+*, calculated by country of residence | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| high > PwMD |

minor > - PwMD |

||

| increased > - PwMD |

low ≤ PwMD | ||

| medium > - PwMD |

|||

| PwMD = People with a Migration background with Dementia *Bulgarien, Litauen, Malta, Polen in der Bevölkerung 60+ |

|||

| Absolute number of PwMD 65+ | |

| PwMD per 100,000 inhabitants 65+ |

Switzerland

At the end of the 19th century, Switzerland developed from an emigration into an immigration country. Since the Second World War, the foreign population has increased continuously, with the exception of the oil crisis in the 1970s and the economic slump in 19831. Until the end of the 1970s, the majority of labour migrants came from Italy and Spain. After the conflicts of the 1990s, an increasing number of people immigrated from countries such as Portugal and Yugoslavia. In recent years, tens of thousands of workers have immigrated from other EU member states2. In 2018, the largest migrant groups originated from Italy, Germany, and Portugal. The migrant population (born abroad) increased tenfold between 1941 and 2019 (223,500 to 2.6 million) and almost doubled between 1990 and 2019 (1.4 million to 2.6 million)3.

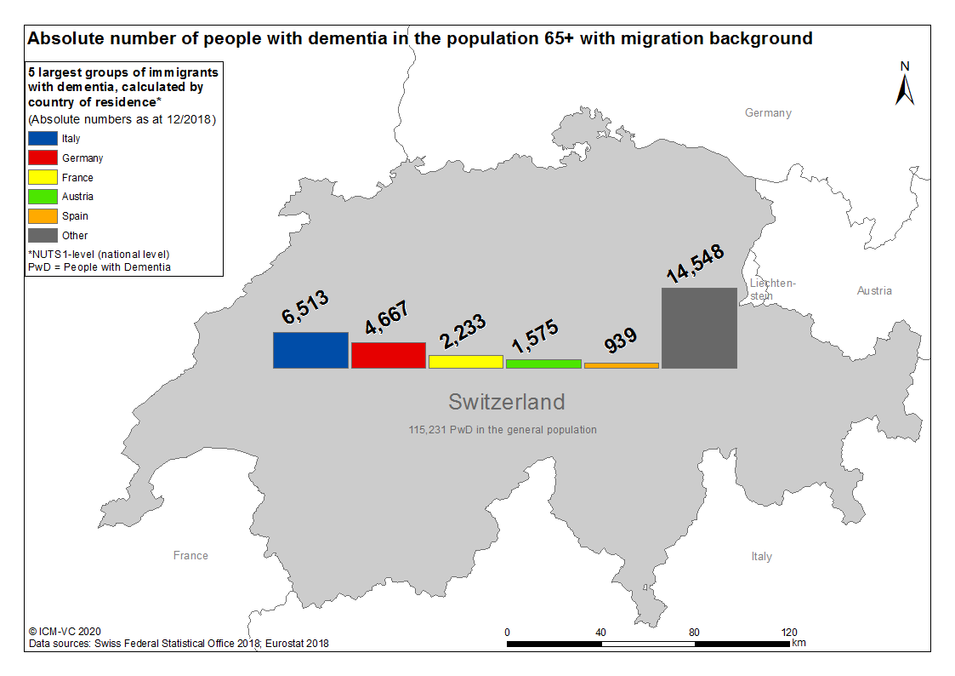

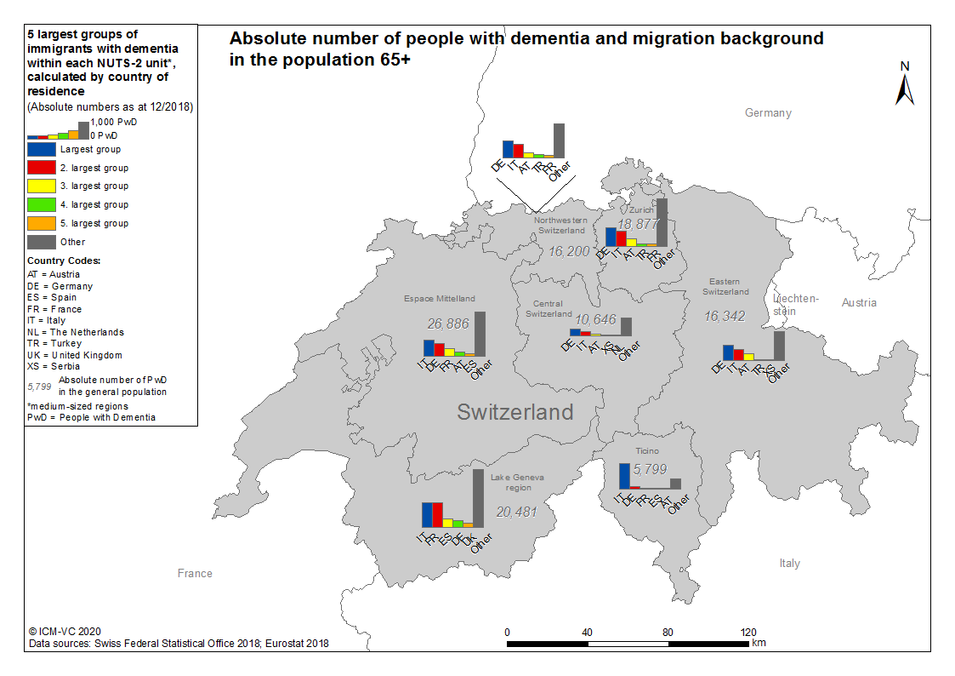

There 368,300 people with a migration background aged 65 or older. Of those, approx. 25,400 are estimated to exhibit some form of dementia. Calculations show the most affected migrant groups presumably originate from Italy (approx. 6,500), Germany (approx. 4,700), France (approx. 2,200), Austria (approx. 1,600), and Spain (approx. 900)4.

The ‘National Dementia Strategy 2014 – 2019’ from 2016 refers briefly to migration in three sub-chapters. It points out that the proportion of migrants in the total population is increasing, especially in the older age groups, which has an impact on the demand for and quality requirements of healthcare services. Furthermore, it is described that in case of PwM, the language barriers pose a particular challenge for dementia diagnosis, as common test procedures are unsuitable or require translation assistance. To address these problems, the existing federal program on migration and health will also include measures related to the topic of dementia5. At the national level, three documents with guidelines, policies, or recommendations were identified for Switzerland:

- the 'Recommendations for the Diagnosis and Treatment of the Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia (BPSD)’ (2014) discusses prevalence, incidence, and phenomenology of BPSD, assessment of BPSD; nursing interventions; person-centered care of people with dementia; and pharmacological and non-pharmacological therapies in dementia among other topics.

- The ‘Medical-Ethical Guidelines: Care and Treatment of People With Dementia’ (2013) addresses the issues of quality of life and well-being, quality of care and treatment, communication with people with dementia, information and consent, dementia diagnosis, appropriate care and treatment, end-of-life decisions, relatives, and research with people with dementia.

- Expert recommendation ‘Dementia: Diagnosis, Treatment and Care’ (2014) addresses dementia, assessment and diagnosis, drug and non-drug treatments, daily living arrangements, support, and care. None of these documents takes migration into account6-8.

References

- Wanner P: Migration und Integration: Ausländerinnen und Ausländer in der Schweiz. In: Eidgenössische Volkszählung 2000. Neuenburg (CH); 2004.

- Nguyen QD: Switzerland, land of European immigration. In., vol. 5; 2017.

- International Organisation for Migration: Total number of international migrants at mid-year 2019: Switzerland; 2019.

- Federal Statistical Office: Statistik der Bevölkerung und der Haushalte. In. Neuchâtel: Federal Statistical Office; 2018.

- Bundesamt für Gesundheit, Schweizerische Konferenz der kantonalen Gesundheitsdirektorinnen und -direktoren: Nationale-Demenzstrategie 2014-2019: Erreichte Resultate 2014-2016 und Prioritäten 2017-2019. In. Bern: Bundesamt für Gesundheit, Schweizerische Konferenz der kantonalen Gesundheitsdirektorinnen und -direktoren; 2016.

- Savaskan E, Bopp-Kistler I, Buerge M, Fischlin R, Georgescu D, Giardini U, Hatzinger M, Hemmeter U, Justiniano I, Kressig RW et al: Empfehlungen zur Diagnostik und Therapie der Behavioralen und Psychologischen Symptome der Demenz (BPSD); 2014.

- Schweizerische Akademie der Medizinischen Wissenschaften: Medizin-ethische Richtlinien: Betreuung und Behandlung von Menschen mit Demenz; 2017.

- Schweizerische Alzheimervereinigung: Demenz: Diagnose, Behandlung und Betreuung. In. Edited by Schweizerische Alzheimervereinigung. Yverdon-les-Bains; 2014.

![[Translate to Englisch:] Logo RBS [Translate to Englisch:] Logo RBS](/fileadmin/_processed_/9/7/csm_RBS_Logo_RGB_0e245a98a4.jpeg)