More than just the movement disorder "St. Vitus' dance"

Huntington's chorea, also called “Huntington’s disease” or "Morbus Huntington", is a dominantly inherited disorder of the brain. It was named after the US physician George Huntington, who was the first to scientifically describe the disease in 1872. Involuntary twitching movements of the head, arms, legs and hands, but also of the trunk, up to a characteristic dance-like gait: in the Middle Ages, these symptoms had earned the disease the now-obsolete name 'St. Vitus' dance'. St. Vitus was invoked as a patron saint in Christian popular belief to cure the disease because, according to legend, he had healed a child from the disease during his lifetime. The characteristic symptoms are also reflected in the name "Huntington's chorea": The term "chorea" is based on the Greek word "choreia" meaning "dance".

Huntington's disease is much more than a movement disorder, however: In the brains of people with Huntington's chorea, areas that are important not only for muscle control but also for mental and cognitive functions gradually deteriorate.

Huntington's chorea is one of the rare diseases: In Germany, about 10,000 people are currently affected by symptoms, women and men alike. Several hundred new cases are diagnosed each year. It is estimated that about 30,000 people in Germany may carry the Huntington's gene. The first symptoms usually appear between the ages of 35 and 50 – more rarely before the age of 20 (juvenile form) or after the age of 60. As of yet, Huntington's is incurable and inevitably leads to death.

Dance-like movements and tantrums

Huntington's disease often begins with rather unspecific symptoms. These include abnormalities in behavior and cognition. Many patients become increasingly irritable, aggressive, depressed, or disinhibited; others become anxious. Typically, those who are affected get impulsive, are prone to outbursts of anger or hurt others for no apparent reason. In addition, there may be massive mistrust and the compulsion to control. Delusions (psychoses) are also part of the range of symptoms.

The movement disorders associated with Huntington's are usually noticeable in involuntary movements, such as of the head, hands, arms, legs, and trunk, and also in tic-like muscle twitches such as blinking of the eyes or a contortion of the mouth. The dance-like gait is typical. As the disease progresses, it becomes increasingly difficult for those affected to coordinate and manage normal, everyday movements. In a small portion of patients, instead of chaotic movements, there is muscle stiffness and inhibited movement. This mainly affects patients with the juvenile form of the disease.

Hasty eating is also typical of the disease. Affected individuals gulp down food as soon as it is placed in front of them, often chewing just a little or not at all. As the disease progresses, control of the tongue and pharyngeal muscles is impaired, making swallowing difficult. In addition, speech disorders occur. Affected individuals often emit involuntary sounds, and later their speech becomes unintelligible.

As the loss of neurons in the brain progresses, mental abilities are also lost, although this can manifest itself individually in different ways, for example through loss of interest, problems of concentration and attention, and forgetfulness. The ability to make judgments diminishes, learning and planning becomes increasingly difficult. Some individuals develop dementia.

Genetic "stuttering"

The cause of the disease is a genetic defect. Huntington's disease is genetic and inherited in an autosomal dominant manner. This means that if an affected parent passes the altered gene on to his or her children, they inevitably also become ill. A region on chromosome number four is affected. Here, there is an area where the DNA building blocks CAG (cytosine, adenine, and guanine) repeat themselves several times – in most people between 10 and 30 times. However, the copying machinery of the genetic material can "stutter" and then the repetitions multiply. After about 36 repetitions the disease gets clinically apparent. The number of repetitions might increase from one generation to the next. The rule of thumb is that the more CAGs, the earlier the onset of the disease and the more rapidly it progresses. Although Huntington's disease is rare in the population overall, it is the most common autosomal dominant inherited neurodegenerative disease that occurs during adulthood.

Approximately one to three percent of all affected individuals have no known family history of Huntington's chorea. In these cases, either it may be a spontaneous alteration in the genetic material or the number of repetitions has exceeded a critical limit from one generation to the next.

The elongated DNA segment causes a protein called Huntingtin to be produced improperly. In its healthy form, Huntingtin is essential to the body. However, the altered form is toxic and causes neurons to die. A few years ago, researchers at the DZNE, together with international colleagues, found out that the defective form of the protein molecule is formed after the Huntingtin gene with an elongated CAG segment is translated into messenger RNA (mRNA). Then a protein complex attaches to the elongated area. As a result, pathogenic Huntingtin is formed, which is too large and clumped together and is deposited in the brain of the diseased person.

As of yet, Huntington's disease is not curable. The individual symptoms can be alleviated by medication as well as non-drug treatments such as ergo therapy or physical therapy.

Understanding the mechanisms

Scientists at the DZNE are working hard to understand the mechanisms by which an elongated CAG region leads to defective Huntingtin. In doing this, they hope to find new targets for therapy and are conducting clinical trials with promising treatment approaches.

In addition, a Germany-wide Huntington's registry is being created: a collection of case data that can also contribute to a better understanding of the disease.

Groundbreaking achievement by a family doctor

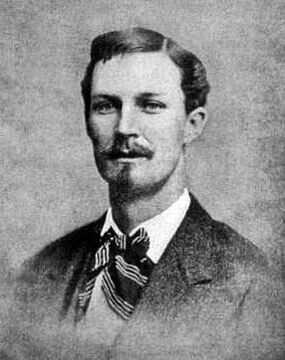

George Huntington (1850–1916) was just eight years old when he first encountered two women suffering from a disease that would later be named after him. Huntington had accompanied his father, who was a general practitioner on Long Island in New York state. The two patients – mother and daughter – were only skin and bones. They moved with a writhing, bent posture, making faces. "From then on, my medical destiny was set," he said many years later during a lecture to the New York Neurological Society.

After graduating from medical school, the young Huntington plunged into his father's and grandfather's patient files, studied their records of the disease, and was the first to recognize the pattern of inheritance, among other things. He himself still believed at the time that it was a localized rarity, often embarrassingly referred to on Long Island as "that disorder." The physician's achievement consisted in particular in recognizing Huntington's disease as an independent, hereditary disease and distinguishing it from other forms of chorea, such as those that can occur after an infection. Huntington chose to pursue a career as a traditional family physician. He later did not deepen his investigations into the disease named after him. It was only in 1993 that the causative genetic defect on chromosome 4 became known and could be detected in a blood test.

Status as of 22.11.2021